Introduction

The rise of music streaming services has fundamentally altered how individuals consume and discover music. This transformation is largely driven by the ubiquitous nature of curated playlists, both algorithmically generated and human-curated. This analysis explores the multifaceted impact of music playlists on listener retention and the discovery of new music within streaming services, drawing upon a diverse range of research. The studies examined utilize various methodologies, including experiments, surveys, and analyses of streaming data, providing a comprehensive, albeit nuanced, understanding of the topic.

The Role of Algorithmic Playlists

Algorithmic playlists, such as Spotify’s Discover Weekly (Derwinis, NaN), (Janice, 2024), (Cole, 2024), represent a significant innovation in music recommendation. These playlists leverage user listening history and data-driven insights to generate personalized recommendations (Derwinis, NaN). However, the effectiveness of these algorithms in fostering listener retention and facilitating new music discovery is a subject of ongoing debate. While some research suggests that algorithmic playlists can successfully introduce users to diverse and relevant music (Lindsay, 2016), others highlight concerns about filter bubbles and echo chambers, where algorithms may reinforce existing preferences rather than expanding musical horizons (Silber, NaN). The study by Katarzyna Derwinis and J. F. Goncalves (Derwinis, NaN) found no significant differences in self-reported use between heavy and light Spotify users. However, it revealed that users who perceived themselves as heavy users enjoyed more diverse content and appreciated algorithmic recommendations more than light users, suggesting that perceived usage may influence the effectiveness of algorithmic playlists. This highlights the importance of considering user perception alongside objective metrics when evaluating the impact of algorithmic curation. Furthermore, the study by Natasha Janice and Nurrani Kusumawati (Janice, 2024) found a significant positive impact of the quality-of-service experience through Discover Weekly on user satisfaction and loyalty to Spotify, directly linking algorithmic playlist quality to user retention.

The effectiveness of algorithmic playlists in driving new music discovery is also influenced by factors beyond the algorithm itself. The subjective organization of songs and genres within a platform’s interface, misrepresentation of songs and artists within genre-based playlists, and the use of user actions (skips, likes, dislikes, etc.) as an assertion of preferences all present challenges (Silber, NaN). These challenges highlight the limitations of relying solely on algorithms for music discovery and underscore the need for a more holistic approach that considers the user experience and the broader context of music consumption. The ACM Recommender Systems Challenge 2018 (Schedl, NaN) further emphasizes the importance of developing sophisticated algorithms for automatic playlist continuation, highlighting the ongoing effort to improve the user experience and engagement through enhanced recommendation systems. This challenge, focused on predicting missing tracks in user-created playlists, directly addresses the problem of seamlessly integrating new music discoveries into established listening habits.

Human Curation and its Impact

In contrast to algorithmic playlists, human-curated playlists offer a different approach to music discovery and listener retention. These playlists are created by music experts or curators who leverage their knowledge and experience to select songs that fit a specific theme or mood (Lindsay, 2016), (Cole, 2024). Research suggests that human-curated playlists provide more consistent recommendations compared to algorithmic curation (Lindsay, 2016), potentially enhancing listener satisfaction and fostering a sense of trust in the platform’s recommendations. The study by C. Lindsay (Lindsay, 2016) found that while human-curated playlists offered more consistent recommendations, algorithmic curation was more effective for discovering new music. This suggests a complementary role for both human and algorithmic approaches in optimizing the user experience. Sebastian Cole and Jessica Yarin Robinson (Cole, 2024) further highlight the importance of human curation in their study of Christmas music playlists, demonstrating how even within a seemingly homogenous genre, users employ playlists as a form of self-expression and individuality, highlighting the interplay between algorithmic and human curation in shaping user experience. The “algotorial” process employed by Spotify (Cole, 2024), a blend of human and algorithmic curation, exemplifies this trend towards integrating both approaches to optimize recommendation effectiveness.

However, the role of human curators is not without its limitations. Concerns exist regarding potential biases and commercial influences that could affect the diversity and representativeness of curated playlists (Silber, NaN), (Cole, 2024). The influence of major labels and the potential for underrepresentation of independent artists or specific genres remain critical considerations (Prey, 2020), (Prey, 2020). Moreover, the opaque nature of playlist curation processes can limit transparency and accountability, raising concerns about potential manipulation or favoritism (Silber, NaN). The research by Robert Prey, Marc Esteve Del Valle, and Leslie R. Zwerwer (Prey, 2020), (Prey, 2020) highlights the significant role of Spotify’s editorial capacity in shaping music discovery and consumption patterns. Their analysis of promotion patterns on Spotify’s Twitter account reveals how the platform’s corporate strategy influences which artists and songs receive prominence, potentially affecting listener retention by promoting certain tracks and artists over others. This underscores the need for greater transparency and a deeper understanding of the factors influencing playlist curation to ensure fairness and diversity.

Playlists and Listener Retention

The relationship between music playlists and listener retention is complex and multifaceted. While effective playlists can enhance user engagement and satisfaction (Janice, 2024), (Cole, 2024), several factors can influence their impact on listener retention. User satisfaction is strongly linked to the quality of the listening experience (Janice, 2024), which is influenced by various factors including the diversity and relevance of recommendations, the ease of navigation, and the overall design of the platform (Gabbolini, 2022). The study by Giovanni Gabbolini and Derek Bridge (Gabbolini, 2022) found that a “Greedy” algorithm generated more liked experiences than an “Optimal” algorithm, suggesting that the specific algorithm used can significantly impact user satisfaction. Key factors for user satisfaction included segue diversity and song arrangement familiarity, indicating that the structural aspects of playlist design are crucial for creating a positive listening experience. Furthermore, the study by Sean Nicolas Brggemann (Brggemann, NaN) highlights the significant role of playlist curators in influencing listener behavior and track demand, emphasizing that effective targeted marketing hinges on identifying the right playlists for promoting tracks. This underscores the importance of playlist curation in driving listener engagement and retention.

However, the impact of playlists on listener retention is not solely determined by the quality of the playlists themselves. Other factors, such as the overall user experience, the availability of other features on the platform, and the listener’s personal preferences, also play a significant role (Walsh, 2024), (Datta, 2017). The research by M. Walsh (Walsh, 2024) explores the phenomenon of background music, demonstrating how streaming services enable users to integrate music into everyday activities, often treating it as background audio. This suggests that while playlists might contribute to overall music consumption, the level of focused engagement with individual tracks might be reduced, potentially affecting the depth of listener connection and retention. The study by Hannes Datta, George Knox, and Bart J. Bronnenberg (Datta, 2017) found that adoption of streaming services leads to increased quantity and diversity of music consumption, but the effects attenuate over time. This suggests that while playlists can initially drive increased engagement, maintaining long-term listener retention requires a more comprehensive strategy. The study also highlights that repeat listening decreases, but the best discoveries have higher rates. This points to the importance of introducing new and engaging music to listeners, suggesting that playlists serve a crucial role in fostering long-term engagement.

Playlists and the Discovery of New Music

Playlists serve as a powerful tool for facilitating the discovery of new music on streaming services. However, the effectiveness of playlists in this regard depends on various factors, including the type of playlist (algorithmic or human-curated), the diversity of the recommendations, and the listener’s existing musical preferences (Silber, NaN), (Lindsay, 2016), (Cole, 2024). The study by C. Lindsay (Lindsay, 2016) found that algorithmic curation is more effective for discovering new music than human curation, suggesting that algorithms can be more successful in introducing users to unfamiliar artists and genres. However, the potential for algorithmic biases and the limitations of relying solely on data-driven recommendations remain a crucial concern (Silber, NaN). The study by Lorenzo Porcaro, Emlia Gmez, and Carlos Castillo (Porcaro, 2023) demonstrates that diverse music recommendations can positively impact listeners’ attitudes towards unfamiliar genres, suggesting that playlists featuring a wide range of music can help listeners overcome pre-existing biases and discover new artists and genres.

The introduction of new music through playlists is also influenced by contextual factors, such as the listener’s emotional state and the specific listening environment (Walsh, 2024), (Ycel, 2022). The research by M. Walsh (Walsh, 2024) highlights how streaming services enable users to integrate music into everyday activities, often as background audio, which may affect their engagement with new music and retention of previously enjoyed tracks. The study by A. Ycel (Ycel, 2022) shows that music preference is associated with emotional state, suggesting that playlists tailored to specific emotions could enhance the discovery and appreciation of new music. The integration of music into diverse everyday activities can expand the role of music beyond focused listening sessions, potentially leading to increased overall music consumption and exposure to diverse genres (Walsh, 2024). However, this increased exposure may also lead to a diminished appreciation for focused listening and silence (Walsh, 2024), potentially impacting the depth of engagement with individual tracks and artists.

The effectiveness of playlists in fostering music discovery is also influenced by the design and presentation of the playlists themselves (Gabbolini, 2022), (Bree, NaN), (Park, 2022). The research by Giovanni Gabbolini and Derek Bridge (Gabbolini, 2022) highlights the importance of factors like segue diversity and song arrangement familiarity in enhancing user satisfaction, suggesting that careful consideration of playlist design can significantly impact the listener’s experience and ability to discover new music. Furthermore, the study by Lotte van Bree, Mark P. Graus, and B. Ferwerda (Bree, NaN) shows that personalized vocabulary in playlist titles significantly influences user decision-making, suggesting that carefully crafted playlist titles can enhance the appeal of playlists and encourage exploration of new music. The research by So Yeon Park and Blair Kaneshiro (Park, 2022) highlights the importance of considering user needs and desires when designing collaborative playlists, emphasizing that features facilitating communication and multiple collaborator editing can enhance user satisfaction and engagement. This further underscores the importance of considering user-centric design principles when creating playlists to optimize their effectiveness in driving music discovery.

The Influence of Platform Strategies

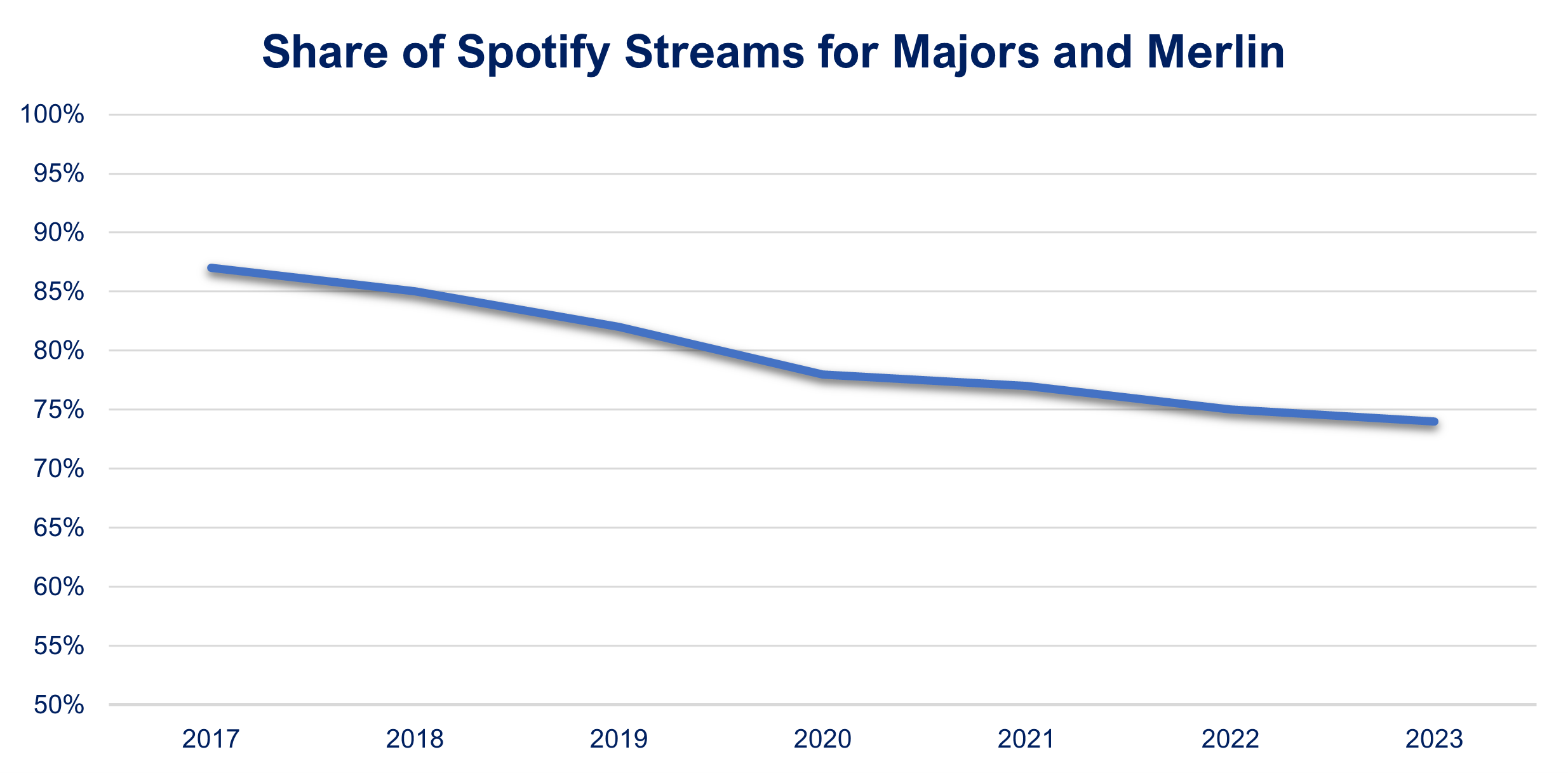

The strategies employed by music streaming platforms significantly impact how playlists influence listener retention and the discovery of new music. Platforms like Spotify actively shape user experience through algorithmic personalization, editorial curation, and targeted marketing (Prey, 2020), (Prey, 2020), (Pedersen, 2020). However, these strategies are not without their limitations and potential drawbacks. The research by Robert Prey, Marc Esteve Del Valle, and Leslie R. Zwerwer (Prey, 2020), (Prey, 2020) highlights the significant role of Spotify’s curated playlists in shaping music discovery and listener retention. Their analysis demonstrates how Spotify’s promotional strategies influence the exposure of major and independent labels, potentially creating a leveling effect in music exposure while simultaneously raising concerns about potential biases and the reinforcement of existing power structures within the music industry. The research by Rasmus Rex Pedersen (Pedersen, 2020) examines Spotify’s data-driven approach to music recommendations, emphasizing the interplay between editorial curation and algorithmic curation in enhancing user experience. This hybrid approach, while aiming for personalization and contextualization, also raises questions about potential biases and the prioritization of user engagement over other considerations. The study by J. Morris (Morris, 2020) further explores the optimization of music for streaming platforms, highlighting the concept of “phonographic effects” where artists adapt their music to be more playlist-friendly, potentially impacting the authenticity and diversity of music available to listeners. The research also touches on artificial play counts and musical spam, highlighting the complex interplay between platform incentives, artist strategies, and user experiences.

The platform’s approach to playlist design and recommendation algorithms also influences user behavior and engagement. The study by Cristina Alaimo and Jannis Kallinikos (Alaimo, 2020) investigates the role of algorithms in categorizing music on platforms like Last.fm, highlighting how algorithmic categorization impacts listeners’ perception and interaction with music, potentially influencing retention and discovery. The research also discusses the transition from expert-driven categorization to algorithm-based systems, emphasizing how this shift affects user engagement with music. The study by Marc Bourreau, Franois Moreau, and Patrik Wikstrm (Bourreau, 2021) analyzes music charts data to assess cultural content changes due to digitization, highlighting a significant increase in diversity with the introduction of Spotify. This suggests that the platform’s design and algorithms can have a significant impact on the diversity of music available to listeners, potentially affecting their ability to discover new music and their overall engagement with the platform. The study by Anthony T. Pinter, Jacob M. Paul, Jessie J. Smith, and Jed R. Brubaker (Pinter, 2020) further emphasizes the interplay between algorithmic curation and expert reviews in shaping music discovery, highlighting the influence of platforms like Pitchfork on listener choices and the subsequent success of artists.

Limitations and Future Research

While this analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the effect of music playlists on listener retention and the discovery of new music, several limitations and areas for future research remain. Many studies focus on specific platforms or genres, limiting the generalizability of findings. The methodologies employed vary across studies, making direct comparisons challenging. Furthermore, the subjective nature of user experience and the complex interplay of factors influencing listener behavior make it difficult to isolate the precise impact of playlists.

Future research should address these limitations by conducting larger-scale, cross-platform studies that incorporate diverse methodologies. More sophisticated analyses of streaming data are needed to better understand the complex relationships between playlist characteristics, user engagement, and retention. Qualitative research, such as in-depth interviews and focus groups, can provide valuable insights into user perceptions and experiences with playlists. Furthermore, research exploring the long-term impacts of playlist exposure on listener preferences and musical tastes is crucial. Investigating the ethical implications of algorithmic personalization and the potential for biases in playlist curation is also essential. Finally, studying the impact of collaborative playlists and the role of social interactions in shaping music discovery and retention warrants further attention.

Music playlists have become an integral part of the music streaming experience, significantly impacting listener retention and the discovery of new music. Algorithmic playlists offer personalized recommendations, potentially exposing listeners to diverse genres and artists. However, concerns remain regarding filter bubbles and echo chambers. Human-curated playlists provide consistent recommendations but may be subject to biases and commercial influences. Effective playlists enhance user engagement and satisfaction, but factors like user experience, platform features, and listening contexts also play a crucial role in listener retention. The strategies employed by streaming platforms significantly influence how playlists shape music discovery and consumption patterns. Future research should address the limitations of existing studies and explore the multifaceted relationships between playlists, user behavior, and the evolving landscape of music streaming. A more holistic approach, integrating quantitative and qualitative methods, is needed to fully understand the complex interplay of factors influencing the impact of music playlists on listener engagement and the ongoing evolution of music discovery.

References

Alaimo, C. & Kallinikos, J. (2020). Managing by data: algorithmic categories and organizing. SAGE Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620934062

Bourreau, M., Moreau, F., & Wikstrm, P. (2021). Does digitization lead to the homogenization of cultural content?. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.13015

Bree, L. V., Graus, M. P., & Ferwerda, B. (NaN). Framing theory on music streaming platforms: how vocabulary influences music playlist decision-making and expectations. None. https://doi.org/None

Brggemann, S. N. (NaN). Effectiveness of targeted digital marketing. None. https://doi.org/10.3929/ETHZ-B-000476394

Cole, S. & Robinson, J. Y. (2024). Curating christmas. M/C Journal. https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.3125

Datta, H., Knox, G., & Bronnenberg, B. J. (2017). Changing their tune: how consumers adoption of online streaming affects music consumption and discovery. Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2017.1051

Derwinis, K. & Goncalves, J. F. (NaN). Do they discover weekly your taste?. None. https://doi.org/None

Gabbolini, G. & Bridge, D. (2022). A user-centered investigation of personal music tours. None. https://doi.org/10.1145/3523227.3546776

Janice, N. & Kusumawati, N. (2024). Harmonizing algorithms and user satisfaction: evaluating the impact of spotify”s discover weekly on customer loyalty. None. https://doi.org/10.58229/jims.v2i2.168

Lindsay, C. (2016). An exploration into how the rise of curation within streaming services has impacted how music fans in the uk discover new music. None. https://doi.org/None

Morris, J. (2020). Music platforms and the optimization of culture. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120940690

Park, S. Y. & Kaneshiro, B. (2022). User perspectives on critical factors for collaborative playlists. Public Library of Science. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260750

Pedersen, R. R. (2020). Datafication and the push for ubiquitous listening in music streaming. Society of Media Researchers In Denmark. https://doi.org/10.7146/mediekultur.v36i69.121216

Pinter, A. T., Paul, J. M., Smith, J. J., & Brubaker, J. R. (2020). P4kxspotify: a dataset of pitchfork music reviews and spotify musical features. None. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v14i1.7355

Porcaro, L., Gmez, E., & Castillo, C. (2023). Assessing the impact of music recommendation diversity on listeners: a longitudinal study. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3608487

Prey, R., Valle, M. E. D., & Zwerwer, L. (2020). Platform pop: disentangling spotifys intermediary role in the music industry. Information, Communication & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1761859

Schedl, M., Zamani, H., Chen, C., Deldjoo, Y., & Elahi, M. (NaN). Recsys challenge 2018 : automatic playlist continuation. None. https://doi.org/None

Silber, J. (NaN). Music recommendation algorithms: discovering weekly or discovering weakly?. None. https://doi.org/10.33767/osf.io/6nqyf

Walsh, M. (2024). It”s mostly an accompaniment to something. M/C Journal. https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.3040

Ycel, A. (2022). The expression of emotions through musical parameters during the covid-19 restrictions: a sentiment analysis on philippines spotify data. Uluslararas Ynetim Biliim Sistemleri ve Bilgisayar Bilimleri Dergisi. https://doi.org/10.33461/uybisbbd.1139568

Geef een reactie

Je moet ingelogd zijn op om een reactie te plaatsen.