Based on Chapter B6 Bob Matthews and Liz Ross

-

How to Cite Other Authors:

A Practical Guide for Media Students

Frank Weissman,

Whether you’re writing a research paper, production report, script analysis, or academic blogpost, citing your sources correctly is essential. In media studies, referencing isn’t just a bureaucratic requirement—it shows academic honesty, strengthens your arguments, and lets others trace your ideas back to reliable sources.

In this guide, you’ll learn the most common citation methods, see side-by-side examples, and understand how to incorporate sources smoothly into your writing.

Why Do We Cite?

You cite to:

- Give credit to original creators

- Strengthen your credibility

- Avoid plagiarism

- Show the depth of your research

- Allow readers to find the original source

Citing properly is a professional skill—one you’ll also use in scriptwriting, journalism, production reports, and academic essays

The Main Citation Method

three ways commonly used in academic writing:

- Direct quotation (short quote)

- Block quotation (long quote)

- Paraphrasing

- Summarising

For each method, you’ll get:

- The original text

- The APA reference

- An example of the correctly cited version in your writing

Direct Quotation (Short Quote)

Use when you want to reproduce the author’s exact words (under 40 words in APA style).

Original Text

“The relationship between audiences and media platforms has fundamentally changed, with participation becoming a key element of modern media cultures.”

(Jenkins, 2006, p. 3)

How to cite it in your text (APA, short quote)

Parenthetical citation:

Media usage has changed significantly, as “participation [has become] a key element of modern media cultures” (Jenkins, 2006, p. 3).

Narrative citation:

Jenkins (2006) argues that “participation [has become] a key element of modern media cultures” (p. 3).

Block Quotation (Long Quote)

Use for quotes 40+ words. The text starts on a new line, indented, without quotation marks.

Original Text (long)

“Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience. Ideally, each medium makes its own unique contribution to the unfolding of the story.”

(Jenkins, 2007, p. 1)

How to cite it in your text (APA, block quote)

Jenkins (2007) describes the concept of transmedia storytelling as:

Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience. Ideally, each medium makes its own unique contribution to the unfolding of the story. (p. 1)

Paraphrasing (Restating in Your Own Words)

Paraphrasing is not shorter; it is expressing the same idea with new wording. Use it most of the time to keep your writing smooth.

Original Text

“Participatory culture shifts the role of audiences from passive consumers to active contributors.”

(Jenkins, 2009, p. 12)

Paraphrased (APA)

In a participatory culture, audiences no longer simply consume content but actively shape and expand it (Jenkins, 2009)

Summarising (Condensing the Idea)

Summaries reduce the original idea to its core message. Useful when you want to capture the broader concept rather than specific wording.

Original Text

In The Long Tail, Anderson argues that digital distribution enables media industries to profit from selling small quantities of a huge number of niche products, rather than relying solely on big hits.

(Anderson, 2004)

Summary (APA)

Anderson (2004) explains that digital markets make it profitable to sell niche products instead of focusing only on mainstream hits.

Tips for Media Students

- Use quotations sparingly—your work should contain more analysis than quoted text.

- Paraphrase when possible; quote only when wording is unique or powerful.

- Always include a reference list at the end.

- Keep track of your sources while researching to avoid confusion later.

Final Reference List (APA 7th Edition)

Anderson, C. (2004). The long tail: Why the Future of Business is selling less of more. Hyperion.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers, and gamers: Exploring participatory culture. New York University Press.

Jenkins, H. (2007). Transmedia storytelling 101. Henry Jenkins Official Blog. https://henryjenkins.org

(If this were a real assignment, include the working URL.)

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. MIT Press.

-

Overview of Laddering Theory

Laddering Theory, Method, Analysis, and Interpretation by Thomas J. Reynolds and Jonathan Gutman is a foundational framework in qualitative research, particularly within consumer behavior studies. Below is an overview of the key aspects of this theory and methodology:

Overview of Laddering Theory

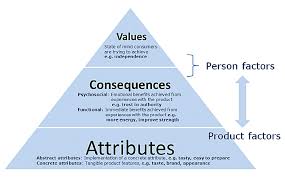

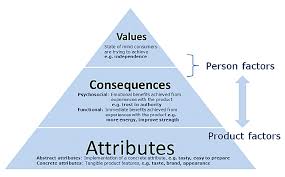

Laddering is a qualitative research technique designed to uncover the deeper motivations, values, and decision-making processes underlying consumer behavior. It is rooted in the Means-End Chain Theory, which posits that consumers make choices based on a hierarchy of perceptions involving three levels:

- Attributes (A): The tangible or intangible features of a product or service.

- Consequences (C): The outcomes or benefits derived from those attributes.

- Values (V): The personal values or life goals that these consequences serve[1][4].

The laddering process seeks to identify the connections between these levels (A → C → V) to understand how products or services align with consumers’ personal values.

Methodology

The laddering technique involves in-depth, one-on-one interviews using a structured probing approach. The primary question format revolves around asking “Why is that important to you?” repeatedly to move from surface-level attributes to deeper values. This process creates a “ladder” of associations for each respondent[1][2][4].

Steps in Laddering:

- Eliciting Attributes: Start by identifying the key features that differentiate a product or service.

- Identifying Consequences: Probe to understand the benefits or outcomes associated with these attributes.

- Uncovering Values: Further probe to reveal the personal values tied to these consequences.

Data Analysis

- Responses are analyzed using content analysis techniques to summarize key elements at each level of abstraction (A, C, V).

- Results are visualized through a Hierarchical Value Map (HVM), which graphically represents the dominant linkages across attributes, consequences, and values[1][4].

Applications

The laddering method has been widely applied in marketing and consumer research to:

- Develop effective branding strategies.

- Understand consumer decision-making processes.

- Identify opportunities for product innovation.

It provides insights into how consumers perceive products in relation to their self-concept and life goals, enabling businesses to align their offerings with consumer values[1][2][6].

Contributions by Reynolds and Gutman

- Thomas J. Reynolds: A professor and researcher specializing in strategic positioning and communication options.

- Jonathan Gutman: A marketing professor focused on developing and applying Means-End Chain methodology.

Their work has been instrumental in advancing both academic and practical applications of laddering as a robust tool for understanding consumer behavior[4].

Citations:

[1] https://is.muni.cz/el/1456/jaro2013/MPH_MVPS/39278324/LadderingTheoy_original.pdf

[2] https://www.data-panda.com/post/laddering-technique-and-5-whys

[3] https://www.businessballs.com/personal-relationships/ladder-theory-of-sexual-relationships/

[4] https://ngovietliem.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Reading-3.3-Laddering-theory.pdf

[5] https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Laddering-theory,-method,-analysis,-and-Reynolds-Gutman/33bef1faa5f75fd54f527f95b9d1e2e4c9dd5b7b

[6] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229053675_Discussing_laddering_application_by_the_means-end_chain_theory

[7] https://asana.com/ko/resources/ladder-of-inference

[8] https://www.studocu.com/it/document/universita-di-bologna/marketing/reynoldsladderingtheory/8042519

[9] https://media.almashhad.com/archive/1698749822629_wEaGz.pdf

[10] https://thesystemsthinker.com/the-ladder-of-inference/ -

Loss Aversion in Marketing:

Loss aversion, a cornerstone of behavioral economics, profoundly impacts consumer decision-making in marketing. It describes the tendency for individuals to feel the pain of a loss more strongly than the pleasure of an equivalent gain (Peng, 2025), (Frank, NaN), (Mrkva, 2019). This psychological principle, far from being a niche concept, permeates various aspects of consumer behavior, offering marketers powerful insights into shaping persuasive campaigns and optimizing strategies. This explanation will delve into the intricacies of loss aversion, exploring its neural underpinnings, its manifestation in diverse marketing contexts, and its implications for crafting effective marketing strategies.

Understanding the Neural Basis of Loss Aversion:

The phenomenon isn’t simply a matter of subjective preference; it has a demonstrable biological basis. Neuroscientific research, such as that conducted by Michael Frank, Adriana Galvan, Marisa Geohegan, Eric Johnson, and Matthew Lieberman (Frank, NaN), reveals that distinct neural networks respond differently to potential gains and losses. Their fMRI study showed that a broad neural network, including midbrain dopaminergic regions and their limbic and cortical targets, exhibited increasing activity as potential gains increased. Conversely, an overlapping set of regions showed decreasing activity as potential losses increased (Frank, NaN). This asymmetry in neural response underscores the heightened sensitivity to potential losses, providing a neurological foundation for the behavioral phenomenon of loss aversion. Further research by C. Eliasmith, A. Litt, and Paul Thagard (Eliasmith, NaN) delves into the interplay between cognitive and affective processes, suggesting a modulation of reward valuation by emotional arousal, influenced by stimulus saliency (Eliasmith, NaN). Their model proposes a dopamine-serotonin opponency in reward prediction error, influencing both cognitive planning and emotional state (Eliasmith, NaN). This neural model offers a biologically plausible explanation for the disproportionate weight given to losses in decision-making. The work of Benedetto De Martino, Colin F. Camerer, and Ralph Adolphs (Martino, 2010) further supports this neurobiological connection by demonstrating that individuals with amygdala damage exhibit reduced loss aversion (Martino, 2010), highlighting the amygdala’s crucial role in processing and responding to potential losses. The study by Zoe Guttman, D. Ghahremani, J. Pochon, A. Dean, and E. London (Guttman, 2021) adds another layer to this understanding by linking age-related changes in the posterior cingulate cortex thickness to variations in loss aversion (Guttman, 2021). This highlights the complex interplay between biological factors, cognitive processes, and the manifestation of loss aversion.

Loss Aversion in Marketing Contexts:

The implications of loss aversion are far-reaching in marketing. Marketers can leverage this bias to enhance consumer engagement and drive sales (Peng, 2025), (Zheng, 2024). Kedi Peng’s research (Peng, 2025) highlights the effectiveness of framing choices to emphasize potential losses rather than gains (Peng, 2025). For instance, promotional sales often emphasize the limited-time nature of discounts, creating a sense of urgency and fear of missing out (FOMO), thereby triggering a stronger response than simply highlighting the potential gains (Peng, 2025), (Zheng, 2024). This FOMO taps directly into loss aversion, motivating consumers to make impulsive purchases to avoid perceived losses (Peng, 2025), (Zheng, 2024), (Hwang, 2024). Luojie Zheng’s work (Zheng, 2024) further underscores the power of loss aversion in attracting and retaining customers (Zheng, 2024), demonstrating its effectiveness in both short-term sales boosts and long-term customer relationship building (Zheng, 2024). The application extends beyond promotional sales. Money-back guarantees and free trials (Soosalu, NaN) capitalize on loss aversion by allowing consumers to experience a product without the immediate commitment of a purchase, reducing the perceived risk of loss (Soosalu, NaN). The feeling of ownership, even partial ownership, can significantly increase perceived value and reduce the likelihood of return (Soosalu, NaN), as consumers become emotionally attached to the product and are averse to losing it (Soosalu, NaN). This principle is also evident in online auctions, where the psychological ownership developed during the bidding process drives prices higher than they might otherwise be (Soosalu, NaN).

Moderators of Loss Aversion:

While loss aversion is a robust phenomenon, its impact is not uniform across all consumers. Several factors can moderate its influence (Mrkva, 2019). Kellen Mrkva, Eric J. Johnson, S. Gaechter, and A. Herrmann (Mrkva, 2019) identified domain knowledge, experience, and education as key moderators (Mrkva, 2019). Consumers with more domain knowledge tend to exhibit lower levels of loss aversion (Mrkva, 2019), suggesting that informed consumers are less susceptible to manipulative marketing tactics that emphasize potential losses. Age also plays a role, with older consumers generally displaying greater loss aversion (Mrkva, 2019), influencing their responses to marketing messages and promotions (Mrkva, 2019). This suggests the need for tailored marketing strategies targeted at different demographic segments, considering their varying levels of susceptibility to loss aversion. The research by Michael S. Haigh and John A. List (Haigh, 2005) further supports this idea by comparing the loss aversion exhibited by professional traders and students (Haigh, 2005). Their findings revealed differences in loss aversion between these groups, highlighting the influence of experience and expertise on this psychological bias (Haigh, 2005). The impact of market share, as highlighted by M. Kallio and M. Halme (Kallio, NaN), also adds another layer of complexity (Kallio, NaN). Their research redefines loss aversion in terms of demand response rather than value response, introducing the concept of a reference price and highlighting market share as a significant factor influencing price behavior (Kallio, NaN). This emphasizes the importance of considering market dynamics and consumer expectations when analyzing loss aversion’s impact.

Loss Aversion and Pricing Strategies:

Loss aversion significantly influences consumer price sensitivity (Genesove, 2001), (Biondi, 2020), (Koh, 2025). David Genesove and Christopher Mayer (Genesove, 2001) demonstrate this in the housing market, where sellers experiencing nominal losses set asking prices significantly higher than expected market values (Genesove, 2001), reflecting their reluctance to realize losses (Genesove, 2001). This reluctance is even more pronounced among owner-occupants compared to investors (Genesove, 2001), highlighting the psychological influence on pricing decisions (Genesove, 2001). Beatrice Biondi and L. Cornelsen (Biondi, 2020) explore the reference price effect in online and traditional supermarkets (Biondi, 2020), finding that loss aversion plays a role in both settings but is less pronounced in online choices (Biondi, 2020). This suggests that the context of the purchase significantly influences the impact of loss aversion on consumer behavior. Daniel Koh and Zulklifi Jalil (Koh, 2025) introduce the Loss Aversion Distribution (LAD) model (Koh, 2025), a novel approach to understanding time-sensitive decision-making behaviors influenced by loss aversion (Koh, 2025). This model provides actionable insights for optimizing pricing strategies by capturing how perceived value diminishes over time, particularly relevant for perishable goods and time-limited offers (Koh, 2025). The work by Botond Kőszegi and Matthew Rabin (Kszegi, 2006) develops a model of reference-dependent preferences, incorporating loss aversion and highlighting how consumer expectations about outcomes impact their willingness to pay (Kszegi, 2006). Their research emphasizes the influence of market price distribution and anticipated behavior on consumer decisions, adding complexity to the understanding of pricing strategies (Kszegi, 2006). The study by Yawen Zhang, B. Li, and Ruidong Zhao (Zhang, 2021) further expands on this by examining the impact of loss aversion on pricing strategies in advance selling, showing that higher loss aversion leads to lower prices (Zhang, 2021).

Loss Aversion and Marketing Messages:

The way information is framed significantly affects consumer responses (Camerer, 2005), (Orivri, 2024), (Chuah, 2011), (Lin, 2023). Colin F. Camerer (Camerer, 2005) emphasizes the importance of prospect theory, where individuals evaluate outcomes relative to a reference point, making losses more impactful than equivalent gains (Camerer, 2005). This understanding is crucial for crafting effective marketing messages (Camerer, 2005). The study by Glory E. Orivri, Bachir Kassas, John Lai, Lisa House, and Rodolfo M. Nayga (Orivri, 2024) explores the impact of gain and loss framing on consumer preferences for gene editing (Orivri, 2024), finding that both frames can reduce aversion but that gain framing is more effective (Orivri, 2024). SweeHoon Chuah and James F. Devlin (Chuah, 2011) highlight the importance of understanding loss aversion in improving marketing strategies for financial services (Chuah, 2011). Jingwen Lin’s research (Lin, 2023) emphasizes the influence of various cognitive biases, including loss aversion, on consumer decision-making, illustrating real-world cases where loss aversion has affected consumer choices (Lin, 2023). This research underscores the significance of addressing cognitive biases like loss aversion to improve decision-making in marketing contexts (Lin, 2023). The research by Mohammed Abdellaoui, Han Bleichrodt, and Corina Paraschiv (Abdellaoui, 2007) further emphasizes the importance of accurately measuring utility for both gains and losses to create effective marketing tactics (Abdellaoui, 2007). Their parameter-free measurement of loss aversion within prospect theory provides a more nuanced understanding of consumer preferences (Abdellaoui, 2007). The study by Peter Sokol-Hessner, Ming Hsu, Nina G. Curley, Mauricio R. Delgado, Colin F. Camerer, and Elizabeth A. Phelps (SokolHessner, 2009) suggests that perspective-taking strategies can reduce loss aversion, implying that reframing losses can influence consumer choices (SokolHessner, 2009). This highlights the potential for marketers to use cognitive strategies to mitigate the negative impact of loss aversion. The research by Ola Andersson, Hkan J. Holm, Jean-Robert Tyran, and Erik Wärneryd (Andersson, 2014) further supports this by showing that deciding for others reduces loss aversion (Andersson, 2014), suggesting that framing decisions in a social context might also alleviate the impact of this bias (Andersson, 2014).

Loss Aversion across Generations and Demographics:

Loss aversion is not experienced uniformly across all demographics. Thomas Edward Hwang’s research (Hwang, 2024) explores generational differences in loss aversion and responses to limited-time discounts (Hwang, 2024). Their findings highlight varying levels of impulse buying and calculated decision-making across Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z, influenced by urgency marketing (Hwang, 2024). This underscores the importance of tailoring marketing strategies to resonate with generational preferences and sensitivities to loss (Hwang, 2024). Aaryan Kayal’s study (Kayal, 2024) specifically addresses cognitive biases, including loss aversion, in the financial decisions of teenagers (Kayal, 2024), highlighting the importance of understanding loss aversion when designing marketing strategies targeted at younger demographics (Kayal, 2024). Simon Gaechter, Eric J. Johnson, and Andreas Herrmann (Gaechter, 2007) found a significant correlation between loss aversion and demographic factors such as age, income, and wealth (Gaechter, 2007), indicating that marketing strategies should be tailored to specific consumer segments based on these factors (Gaechter, 2007). Sudha V Ingalagi and Mamata (Ingalagi, 2024) also investigated the influence of gender and risk perception on loss aversion in investment decisions, suggesting that similar principles could be applied to consumer behavior in marketing contexts (Ingalagi, 2024). Their research highlights the importance of considering these variables when designing marketing campaigns (Ingalagi, 2024). The research by J. Nicolau, Hakseung Shin, Bora Kim, and J. F. O’Connell (Nicolau, 2022) demonstrates how loss aversion impacts passenger behavior in airline pricing strategies, with business passengers showing a greater reaction to loss aversion than economy passengers (Nicolau, 2022). This suggests that different customer segments exhibit varying degrees of sensitivity to losses, impacting the effectiveness of marketing strategies (Nicolau, 2022).

Loss Aversion in Specific Marketing Scenarios:

The principle of loss aversion finds application in various marketing scenarios beyond simple pricing and promotional strategies. The research by Wentao Zhan, Wenting Pan, Yi Zhao, Shengyu Zhang, Yimeng Wang, and Minghui Jiang (Zhan, 2023) explores how loss aversion affects customer decisions regarding return-freight insurance (RI) in e-retailing (Zhan, 2023). Their findings indicate that higher loss sensitivity leads to reduced willingness to purchase RI, impacting e-retailer profitability (Zhan, 2023). This highlights the importance of considering loss aversion when designing return policies and insurance options (Zhan, 2023). Qin Zhou, Kum Fai Yuen, and Yu-ling Ye (Zhou, 2021) examine the impact of loss aversion and brand loyalty on competitive trade-in strategies (Zhou, 2021), showing that firms recognizing consumer loss aversion can increase profits compared to those that don’t (Zhou, 2021). However, they also find that both loss aversion and brand loyalty negatively affect consumer surplus (Zhou, 2021), suggesting a complex interplay between business strategies and consumer welfare (Zhou, 2021). The research by Junjie Lin (Lin, 2024) explores the impact of loss aversion in real estate and energy conservation decisions (Lin, 2024), demonstrating how the fear of loss influences consumer choices in these areas (Lin, 2024). This suggests that similar principles might apply to other marketing fields where consumers make significant financial commitments (Lin, 2024). The study by Jiaying Xu, Qingfeng Meng, Yuqing Chen, and Zhao Jia (Xu, 2023) examines loss aversion’s impact on pricing decisions in product recycling within green supply chain operations (Xu, 2023), demonstrating that understanding consumer loss aversion can improve economic efficiency and resource conservation in marketing efforts (Xu, 2023). This highlights the applicability of loss aversion principles to sustainable marketing practices (Xu, 2023). The study by Yashi Lin, Jiaxuan Wang, Zihao Luo, Shaojun Li, Yidan Zhang, and B. Wünsche (Lin, 2023) investigates how loss aversion can be used to increase physical activity in augmented reality (AR) exergames (Lin, 2023), suggesting that this principle can be applied beyond traditional marketing contexts to encourage healthy behaviors (Lin, 2023). The research by Roland G. Fryer, Steven D. Levitt, John A. List, and Sally Sadoff (Fryer, 2012) demonstrates the effectiveness of pre-paid incentives leveraging loss aversion to improve teacher performance (Fryer, 2012), which highlights the potential of this principle in motivational contexts beyond consumer marketing (Fryer, 2012). Zhou Yong-wu and L. Ji-cai (Yong-wu, NaN) analyze the joint decision-making process of loss-averse retailers regarding advertising and order quantities (Yong-wu, NaN), showing that loss aversion influences both advertising spending and inventory management (Yong-wu, NaN). This suggests that loss aversion impacts various aspects of retail marketing strategies (Yong-wu, NaN). Lei Jiang’s research (Jiang, 2018), (Jiang, 2018), (Jiang, NaN) consistently explores the impact of loss aversion on retailers’ decision-making processes, analyzing advertising strategies in both cooperative and non-cooperative scenarios (Jiang, 2018), (Jiang, 2018), (Jiang, NaN) and highlighting how loss aversion influences order quantities and advertising expenditures (Jiang, 2018), (Jiang, NaN). This work consistently demonstrates the pervasive influence of loss aversion on various aspects of retail marketing and supply chain management. The research by Shaofu Du, Huifang Jiao, Rongji Huang, and Jiaang Zhu (Du, 2014) examines supplier decision-making behaviors during emergencies, considering consumer risk perception and loss aversion (Du, 2014). Although not directly focused on marketing, it highlights the broader impact of loss aversion on decision-making under conditions of uncertainty (Du, 2014). C. Lan and Jianfeng Zhu (Lan, 2021) explore the impact of loss aversion on consumer decisions in new product presale strategies in the e-commerce supply chain (Lan, 2021), demonstrating that understanding loss aversion can inform optimal pricing strategies (Lan, 2021). This research highlights the importance of considering consumer psychology when designing presale campaigns (Lan, 2021). The research by Shuang Zhang and Yueping Du (Zhang, 2025) applies evolutionary game theory to analyze dual-channel pricing decisions, incorporating consumer loss aversion (Zhang, 2025). Their findings suggest that a decrease in consumer loss aversion leads to more consistent purchasing behavior, impacting manufacturers’ strategies (Zhang, 2025). This study demonstrates the importance of considering behavioral economics in marketing tactics (Zhang, 2025). The study by R. Richardson (Richardson, NaN) examines the moderating role of social networks on loss aversion, highlighting how socially embedded exchanges amplify the effects of loss aversion on consumer-brand relationships (Richardson, NaN). This research underscores the importance of understanding social influence when designing marketing strategies that consider loss aversion (Richardson, NaN). Finally, Hanshu Zhuang’s work (Zhuang, 2023) explores the relationship between customer loyalty and status quo bias, which is closely tied to loss aversion, highlighting the importance of considering loss aversion when designing loyalty programs and marketing strategies that aim to retain customers (Zhuang, 2023).

Addressing Loss Aversion in Marketing Strategies:

Understanding loss aversion allows marketers to design more effective campaigns. By framing messages to emphasize potential losses, marketers can tap into consumers’ heightened sensitivity to negative outcomes, driving stronger responses than simply highlighting potential gains (Peng, 2025), (Zheng, 2024). This approach can be applied to various marketing elements, including pricing, promotions, and product messaging. However, it’s crucial to employ ethical and responsible marketing practices, avoiding manipulative tactics that exploit consumer vulnerabilities (Zamfir, 2024), (Dam, NaN). The research by Y. K. Dam (Dam, NaN) suggests that negative labelling (highlighting potential losses from unsustainable consumption) can be more effective than positive labelling (highlighting gains from sustainable consumption) in promoting sustainable consumer behavior (Dam, NaN). This research emphasizes the importance of understanding the psychological mechanisms behind consumer choices when designing marketing strategies that promote socially responsible behaviors (Dam, NaN). The paper by Christopher McCusker and Peter J. Carnevale (McCusker, 1995) examines how framing resource dilemmas influences decision-making and cooperation, highlighting the impact of loss aversion on cooperative behavior (McCusker, 1995). This research suggests that understanding loss aversion can improve marketing approaches and decision-making in various fields (McCusker, 1995). The study by Midi Xie (Xie, 2023) investigates the influence of status quo bias and loss aversion on consumer choices, using the Coca-Cola’s new Coke launch as a case study (Xie, 2023). This research emphasizes the importance of considering consumer reluctance to change when introducing new products (Xie, 2023). The research by Peter Sokol-Hessner, Colin F. Camerer, and Elizabeth A. Phelps (SokolHessner, 2012) indicates that emotion regulation strategies can reduce loss aversion (SokolHessner, 2012), suggesting that marketers can potentially influence consumers’ emotional responses to mitigate the impact of loss aversion (SokolHessner, 2012). The research by K. Selim, A. Okasha, and Heba M. Ezzat (Selim, 2015) explores loss aversion in the context of asset pricing and financial markets, finding that loss aversion can improve market quality and stability (Selim, 2015). While not directly related to marketing, this research suggests that understanding loss aversion can lead to more stable and efficient market outcomes (Selim, 2015). The study by Michael Neel (Neel, 2025) examines the impact of country-level loss aversion on investor responses to earnings news, finding that investors in more loss-averse countries are more sensitive to bad news (Neel, 2025). Although not directly marketing-related, this research illustrates the cross-cultural variations in loss aversion and its implications for investment decisions (Neel, 2025). The work by Artina Kamberi and Shenaj Haxhimustafa (Kamberi, 2024) investigates the impact of loss aversion on investment decision-making, considering demographic factors and financial literacy (Kamberi, 2024). While not directly marketing-focused, this research provides insights into how loss aversion influences risk preferences and investment choices (Kamberi, 2024). Finally, the research by Glenn Dutcher, Ellen Green, and B. Kaplan (Dutcher, 2020) explores how framing (gain vs. loss) in messages influences decision-making regarding organ donations (Dutcher, 2020), demonstrating the effectiveness of loss-framed messages in increasing commitment to donation (Dutcher, 2020). This highlights the power of framing in influencing decisions, a principle applicable to various marketing contexts (Dutcher, 2020). The research by Qi Wang, L. Wang, Xiaohang Zhang, Yunxia Mao, and Peng Wang (Wang, 2017) examines how the presentation of online reviews can evoke loss aversion, affecting consumer purchase intention and delay (Wang, 2017). This work highlights the importance of considering the psychological impact of information presentation when designing online marketing strategies (Wang, 2017). The research by Mauricio R. Delgado, A. Schotter, Erkut Y. Ozbay, and E. Phelps (Delgado, 2008) investigates why people overbid in auctions, linking it to the neural circuitry of reward and loss contemplation (Delgado, 2008). This research demonstrates how framing options to emphasize potential loss can heighten bidding behavior, illustrating principles of loss aversion in a tangible context (Delgado, 2008). Finally, the research by Zhilin Yang and Robin T. Peterson (Yang, 2004) examines the moderating effects of switching costs on customer satisfaction and perceived value, which can indirectly relate to loss aversion as switching costs can represent a perceived loss for customers (Yang, 2004).

Loss aversion is a powerful and pervasive psychological force that significantly influences consumer behavior in marketing. Understanding its neural underpinnings and its manifestation across various contexts, demographics, and marketing strategies is essential for creating effective and ethical campaigns. By acknowledging and strategically addressing loss aversion, marketers can design more persuasive messages, optimize pricing strategies, and foster stronger consumer engagement. However, it is equally crucial to employ these insights responsibly, avoiding manipulative tactics that exploit consumer vulnerabilities. A thorough understanding of loss aversion empowers marketers to create campaigns that resonate deeply with consumers while upholding ethical standards. Further research into the nuances of loss aversion, its interaction with other cognitive biases, and its cross-cultural variations will continue to refine our understanding and its application in marketing.

References

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., & Paraschiv, C. (2007). Loss aversion under prospect theory: a parameter-free measurement. Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1070.0711

Andersson, O., Holm, H. J., Tyran, J., & Wengstrm, E. (2014). Deciding for others reduces loss aversion. Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.2085

Biondi, B. & Cornelsen, L. (2020). Reference price effect on consumer choicein online and traditional supermarkets: anapplication of discrete choice model onhome scan data. None. https://doi.org/10.6092/UNIBO/AMSACTA/6424

Camerer, C. F. (2005). Three cheerspsychological, theoretical, empiricalfor loss aversion. SAGE Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.42.2.129.62286

Chuah, S. & Devlin, J. F. (2011). Behavioural economics and financial services marketing: a review. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321111165257

Dam, Y. K. (NaN). Sustainable consumption and marketing. None. https://doi.org/10.18174/370623

Delgado, M. R., Schotter, A., Ozbay, E. Y., & Phelps, E. (2008). Understanding overbidding: using the neural circuitry of reward to design economic auctions. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158860

Du, S., Jiao, H., Huang, R., & Zhu, J. (2014). Emergency-dependent supply decisions with risk perception and price control. None. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/965395

Dutcher, G., Green, E., & Kaplan, B. (2020). Using behavioral economics to increase transplantation through commitments to donate.. Transplantation. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000003182

Eliasmith, C., Litt, A., & Thagard, P. (NaN). Why losses loom larger than gains: modeling neural mechanisms of cognitive-affective interaction. None. https://doi.org/None

Frank, M., Galvan, A., Geohegan, M., Johnson, E., & Lieberman, M. (NaN). Supplementary materials for : losses loom larger than gains in the brain : neural loss aversion predicts behavioral loss aversion. None. https://doi.org/None

Fryer, R. G., Levitt, S. D., List, J. A., & Sadoff, S. (2012). Enhancing the efficacy of teacher incentives through loss aversion: a field experiment. None. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18237

Gaechter, S., Johnson, E. J., & Herrmann, A. (2007). Individual-level loss aversion in riskless and risky choices. RELX Group (Netherlands). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1010597

Genesove, D. & Mayer, C. (2001). Loss aversion and seller behavior: evidence from the housing market. None. https://doi.org/10.3386/w8143

Guttman, Z., Ghahremani, D., Pochon, J., Dean, A., & London, E. (2021). Age influences loss aversion through effects on posterior cingulate cortical thickness. Frontiers in Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.673106

Haigh, M. S. & List, J. A. (2005). Do professional traders exhibit myopic loss aversion? an experimental analysis. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00737.x

Hwang, T. E. (2024). Generational variations in loss aversion: analyzing purchase decisions under limited-time discounts. Journal of World Economy. https://doi.org/10.56397/jwe.2024.12.05

Ingalagi, S. V. & Mamata, (2024). Implications of loss aversion and investment decisions. None. https://doi.org/10.61808/jsrt90

Jiang, L. (2018). Cooperative advertising and order strategy between the risk neutral manufacturer and the loss averse retailer. International Conferences on Computers in Management and Business. https://doi.org/10.1145/3232174.3232188

Jiang, L. (2018). Game in two kinds of situations based on the loss averse retailer. None. https://doi.org/10.1145/3271972.3271999

Jiang, L. (NaN). Supply chain cooperative advertising and ordering model for the loss averse retailer. None. https://doi.org/10.17706/IJAPM.2018.8.3.31-44

Kallio, M. & Halme, M. (NaN). Redefining loss averse and gain seeking. None. https://doi.org/None

Kamberi, A. & Haxhimustafa, S. (2024). Loss aversion: the unseen force shaping investment decisions. None. https://doi.org/10.62792/ut.evision.v11.i21-22.p2705

Kayal, A. (2024). Cognitive biases in financial decisions made by teenagers. INTERANTIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT. https://doi.org/10.55041/ijsrem37474

Koh, D. & Jalil, Z. (2025). An application framework for the loss aversion distribution: insights for marketing, education, and digital adoption. International journal of business management. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v20n2p1

Kszegi, B. & Rabin, M. (2006). A model of reference-dependent preferences*. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.121.4.1133

Lan, C. & Zhu, J. (2021). New product presale strategies considering consumers loss aversion in the e-commerce supply chain. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8194879

Lin, J. (2023). The impact of anchoring effects, loss aversion, and belief perseverance on consumer decision-making. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/62/20231321

Lin, J. (2024). Exploring the impact and decisions of loss aversion psychology in the real estate field and energy conservation. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/2024.18448

Lin, Y., Wang, J., Luo, Z., Li, S., Zhang, Y., & Wnsche, B. (2023). Dragon hunter: loss aversion for increasing physical activity in ar exergames. Australasian Computer Science Week. https://doi.org/10.1145/3579375.3579403

Martino, B. D., Camerer, C. F., & Adolphs, R. (2010). Amygdala damage eliminates monetary loss aversion. National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910230107

McCusker, C. & Carnevale, P. J. (1995). Framing in resource dilemmas: loss aversion and the moderating effects of sanctions. Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1995.1015

Mrkva, K., Johnson, E. J., Gaechter, S., & Herrmann, A. (2019). Moderating loss aversion: loss aversion has moderators, but reports of its death are greatly exaggerated. None. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1156

Neel, M. (2025). Country-level loss aversion and the market response to earnings news. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4768248

Nicolau, J., Shin, H., Kim, B., & O”Connell, J. F. (2022). The impact of loss aversion and diminishing sensitivity on airline revenue: price sensitivity in cabin classes. Journal of Travel Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875221093014

Orivri, G. E., Kassas, B., Lai, J., House, L., & Nayga, R. M. (2024). The impacts of message framing on consumer preferences for gene editing. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics-Revue Canadienne D”Agroeconomie. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12380

Peng, K. (2025). The impact of loss aversion on decision-making in marketing and financial markets. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/2024.19247

Richardson, R. (NaN). The moderating role of social networks in loss aversion: testing how consumption in network subcultures can strengthen consumer-brand relationships. None. https://doi.org/None

Selim, K., Okasha, A., & Ezzat, H. M. (2015). Loss aversion, adaptive beliefs, and asset pricing dynamics. Advances in Decision Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/971269

SokolHessner, P., Camerer, C. F., & Phelps, E. A. (2012). Emotion regulation reduces loss aversion and decreases amygdala responses to losses. University of Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nss002

SokolHessner, P., Hsu, M., Curley, N. G., Delgado, M. R., Camerer, C. F., & Phelps, E. A. (2009). Thinking like a trader selectively reduces individuals” loss aversion. National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0806761106

Soosalu, G. (NaN). O-prime, a new semantic tool. None. https://doi.org/None

Wang, Q., Wang, L., Zhang, X., Mao, Y., & Wang, P. (2017). The impact research of online reviews” sentiment polarity presentation on consumer purchase decision. Information Technology and People. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-06-2014-0116

Xie, M. (2023). The influence of status quo bias on the behavior of micro subject. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/10/20230434

Xu, J., Meng, Q., Chen, Y., & Jia, Z. (2023). Dual-channel pricing decisions for product recycling in green supply chain operations: considering the impact of consumer loss aversion. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031792

Yang, Z. & Peterson, R. T. (2004). Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: the role of switching costs. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20030

Yong-wu, Z. & Ji-cai, L. (NaN). Joint decision-making of order quantities and advertising expenditure for loss-averse retailers. None. https://doi.org/None

Zamfir, M. D. (2024). Scarcity effect and consumer decision biases: how urgency influences the perceived value of products. Journal of World Economy. https://doi.org/10.56397/jwe.2024.12.04

Zhan, W., Pan, W., Zhao, Y., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., & Jiang, M. (2023). The optimal decision of e-retailer based on return-freight insurance – considering the loss aversion of customers. Kybernetes. https://doi.org/10.1108/k-07-2023-1187

Zhang, S. & Du, Y. (2025). Application of evolutionary game to analyze dual-channel decisions: taking consumer loss aversion into consideration. Mathematics. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13020234

Zhang, Y., Li, B., & Zhao, R. (2021). Resale or agency: pricing strategy for advance selling in a supply chain considering consumers loss aversion. None. https://doi.org/10.1093/IMAMAN/DPAB012

Zheng, L. (2024). The power of loss aversion: enhancing customer engagement and retention in business. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/2024.18268

Zhou, Q., Yuen, K. F., & Ye, Y. (2021). The effect of brand loyalty and loss aversion on competitive trade-in strategies. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2021.1933423

Zhuang, H. (2023). Customer loyalty and status quo bias. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/12/20230655

-

Writing a Research Report

A research report is a structured document that presents the findings of a study or investigation. It typically consists of several key parts, each serving a specific purpose in communicating the research process and results.

The report begins with a title page, which includes the title of the research, author’s name, and institutional affiliation. Following this is an abstract, a concise summary of the entire paper, highlighting the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions. This provides readers with a quick overview of the study’s significance.

The introduction serves as the foundation of the report, presenting the research problem or question, providing relevant background information, and establishing the study’s purpose and significance. It often concludes with a clear thesis statement or research objective.

A literature review typically follows, surveying and evaluating existing research related to the topic. This section helps contextualize the current study within the existing body of knowledge and identifies gaps or areas for further investigation.

The methodology section is crucial, as it explains the research design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques used in the study. It should provide sufficient detail to allow others to replicate the study if desired.

The results section presents the findings of the study, often through text, tables, or figures. It should be objective and organized logically, highlighting key findings and supporting them with appropriate evidence.

The discussion section interprets and analyzes the results, relating them to the research objectives and previous literature. It explores the implications, limitations, and potential future directions of the study.

The conclusion summarizes the main points of the research paper, restates the thesis or research objective, and discusses the overall significance of the findings[4]. It should leave the reader with a clear understanding of the study’s contributions[4].

Finally, the report includes a references section, listing all sources cited in the research paper using a specific citation style. This is essential for acknowledging and giving credit to the works of others.

Some research reports may also include additional sections such as recommendations, which suggest actions based on the findings, and appendices, which provide supplementary information that supports the main text.

I

-

Research Proposals (Chapter B6)

Research proposals play a crucial role in the social sciences, serving as a roadmap for researchers and a tool for gaining approval or funding. Matthews and Ross (2010) emphasize the importance of research proposals in their textbook “Research Methods: A Practical Guide for the Social Sciences,” highlighting their role in outlining the scope, methodology, and significance of a research project.

The choice of research method in social research is a critical decision that depends on various factors, including the research question, available resources, and ethical considerations. Matthews and Ross (2010) discuss several key research methods, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches.

Quantitative methods involve collecting and analyzing numerical data, often using statistical techniques. These methods are particularly useful for testing hypotheses and identifying patterns across large populations. On the other hand, qualitative methods focus on in-depth exploration of phenomena, often using techniques such as interviews, focus groups, or participant observation (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Mixed methods research, which combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches, has gained popularity in recent years. This approach allows researchers to leverage the strengths of both methodologies, providing a more comprehensive understanding of complex social phenomena (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010).

When choosing a research method, researchers must consider the nature of their research question and the type of data required to answer it effectively. For example, a study exploring the prevalence of a particular behavior might be best suited to a quantitative approach, while an investigation into the lived experiences of individuals might benefit from a qualitative methodology.

Ethical considerations also play a significant role in method selection. Researchers must ensure that their chosen method minimizes harm to participants and respects principles such as informed consent and confidentiality (Israel, 2014).

Structure

Introduction: This section sets the stage for your research by introducing the research problem or topic, clearly stating the research question(s), and outlining the objectives of your project3. It also establishes the context and significance of your research, highlighting its potential contributions and who might benefit from its findings

Literature Review: This section demonstrates your understanding of the existing knowledge and research related to your topic4. It involves critically evaluating relevant literature and synthesizing key themes and findings, providing a foundation for your research questions and methodology.

Methodology/Methods: This crucial section details how you plan to conduct your research4. It outlines the research design, the data collection methods you will employ, and the sampling strategy used to select participants or cases5. The methodology should align with your research questions and the type of data needed to address them.

Dissemination: This section describes how you intend to share your research findings with relevant audiences. It may involve outlining plans for presentations, publications, or other forms of dissemination, ensuring the research reaches those who can benefit from it.

Timetable: A clear timetable provides a realistic timeline for your research project, outlining key milestones and deadlines for each stage, including data collection, analysis, and writing6. It demonstrates your understanding of the time required to complete the research successfully.

References:

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Israel, M. (2014). Research ethics and integrity for social scientists: Beyond regulatory compliance. Sage.

Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2010). Research methods: A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson Education.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2010). Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Sage.

Citations:

[1] https://www.bol.com/nl/nl/f/research-methods/39340982/

[2] https://search.worldcat.org/title/Research-methods-:-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/oclc/867911596

[3] https://www.pearson.com/en-gb/subject-catalog/p/research-methods-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/P200000004950/9781408226186

[4] https://search.worldcat.org/title/Research-methods-:-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/oclc/780979587

[5] https://www.studeersnel.nl/nl/document/tilburg-university/methodologie-4-ects/summary-research-methods-bob-matthews-liz-ross/109770

[6] https://books.google.com/books/about/Research_Methods.html?id=g2mpBwAAQBAJ

[7] https://books.google.com/books/about/Research_Methods.html?id=7s4ERAAACAAJ

[8] https://academic.oup.com/bjc/article-abstract/52/5/1017/470134?login=false&redirectedFrom=fulltext -

Data Collection (Part C)

Research Methods in Social Research: A Comprehensive Guide to Data Collection

Part C of “Research Methods: A Practical Guide for the Social Sciences” by Matthews and Ross focuses on the critical aspect of data collection in social research. This section provides a comprehensive overview of various data collection methods, their applications, and practical considerations for researchers.

The authors emphasize that data collection is a practical activity, building upon the concept of data as a representation of social reality (Matthews & Ross, 2010). They introduce three key continua to help researchers select appropriate tools for their studies:

- Structured/Semi-structured/Unstructured Data

- Present/Absent Researcher

- Active/Passive Researcher

These continua highlight the complexity of choosing data collection methods, emphasizing that it’s not a simple binary decision but rather a nuanced process considering multiple factors[1].

The text outlines essential data collection skills, including record-keeping, format creation, note-taking, communication skills, and technical proficiency. These skills are crucial for ensuring the quality and reliability of collected data[1].

Chapters C3 through C10 explore specific data collection methods in detail:

- Questionnaires: Widely used for collecting structured data from large samples[1].

- Semi-structured Interviews: Offer flexibility for gathering in-depth data[1].

- Focus Groups: Leverage group dynamics to explore attitudes and opinions[1].

- Observation: Involves directly recording behaviors in natural settings[1].

- Narrative Data: Focuses on collecting and analyzing personal stories[1].

- Documents: Valuable sources for insights into past events and social norms[1].

- Secondary Sources of Data: Utilizes existing datasets and statistics[1].

- Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC): Explores new avenues for data collection in the digital age[1].

Each method is presented with its advantages, disadvantages, and practical considerations, providing researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for data collection.

The choice of research method in social research depends on various factors, including the research question, the nature of the data required, and the resources available. As Bryman (2016) notes in “Social Research Methods,” the selection of a research method should be guided by the research problem and the specific aims of the study[2].

Creswell and Creswell (2018) in “Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches” emphasize the importance of aligning the research method with the philosophical worldview of the researcher and the nature of the inquiry[3]. They argue that the choice between qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods approaches should be informed by the research problem and the researcher’s personal experiences and worldviews.

Part C of Matthews and Ross’s “Research Methods: A Practical Guide for the Social Sciences” provides a comprehensive foundation for understanding and implementing various data collection methods in social research. By considering the three key continua and exploring the range of available methods, researchers can make informed decisions about the most appropriate approaches for their specific research questions and contexts.

References:

Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2010). Research methods: A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson Education.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Citations:

[1] https://www.bol.com/nl/nl/f/research-methods/39340982/

[2] https://search.worldcat.org/title/Research-methods-:-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/oclc/867911596

[3] https://www.pearson.com/en-gb/subject-catalog/p/research-methods-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/P200000004950/9781408226186

[4] https://search.worldcat.org/title/Research-methods-:-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/oclc/780979587

[5] https://www.studeersnel.nl/nl/document/tilburg-university/methodologie-4-ects/summary-research-methods-bob-matthews-liz-ross/109770

[6] https://books.google.com/books/about/Research_Methods.html?id=g2mpBwAAQBAJ

[7] https://books.google.com/books/about/Research_Methods.html?id=7s4ERAAACAAJ

[8] https://academic.oup.com/bjc/article-abstract/52/5/1017/470134?login=false&redirectedFrom=fulltext -

Research Design (Chapter B3)

Research Methods in Social Research: Choosing the Right Approach

The choice of research method in social research is a critical decision that shapes the entire study. Matthews and Ross (2010) emphasize the importance of aligning the research method with the research questions and objectives. They discuss various research methods, including experimental designs, quasi-experimental designs, cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies, and case studies.

Experimental designs, while offering strong causal inferences, are often challenging to implement in social research due to the complexity of real-world situations[1]. Quasi-experimental designs provide a more practical alternative, allowing researchers to approximate experimental conditions in natural settings[1].

Cross-sectional studies offer a snapshot of a phenomenon at a specific point in time, useful for describing situations or comparing groups[1]. In contrast, longitudinal studies track changes over time, providing insights into trends and potential causal relationships[1]. However, as Bryman (2016) notes, longitudinal studies can be resource-intensive and may face challenges with participant attrition over time[2].

Case studies, as highlighted by Yin (2018), offer in-depth exploration of specific instances, providing rich, contextual data[3]. While case studies may lack broad generalizability, they can offer valuable insights into complex social phenomena[3].

The choice of research method should be guided by several factors:

- Research questions and objectives

- Available resources and time constraints

- Ethical considerations

- Nature of the phenomenon being studied

- Desired level of generalizability

Creswell and Creswell (2018) emphasize the growing importance of mixed methods research, which combines qualitative and quantitative approaches to provide a more comprehensive understanding of social phenomena[4].

The selection of research method in social research is a nuanced decision that requires careful consideration of multiple factors. As Matthews and Ross (2010) stress, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and researchers must critically evaluate the strengths and limitations of each method in relation to their specific research context[1].

References:

Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2010). Research methods: A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson Education.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Citations:

[1] https://www.bol.com/nl/nl/f/research-methods/39340982/

[2] https://search.worldcat.org/title/Research-methods-:-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/oclc/867911596

[3] https://www.pearson.com/en-gb/subject-catalog/p/research-methods-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/P200000004950/9781408226186

[4] https://search.worldcat.org/title/Research-methods-:-a-practical-guide-for-the-social-sciences/oclc/780979587

[5] https://www.studeersnel.nl/nl/document/tilburg-university/methodologie-4-ects/summary-research-methods-bob-matthews-liz-ross/109770

[6] https://books.google.com/books/about/Research_Methods.html?id=g2mpBwAAQBAJ

[7] https://books.google.com/books/about/Research_Methods.html?id=7s4ERAAACAAJ

[8] https://academic.oup.com/bjc/article-abstract/52/5/1017/470134?login=false&redirectedFrom=fulltext -

Choosing Method(Chapter B4)

The choice of research method in social research is a critical decision that shapes the entire research process. Matthews and Ross (2010) emphasize the importance of aligning research methods with research questions and objectives. This alignment ensures that the chosen methods effectively address the research problem and yield meaningful results.

Quantitative and qualitative research methods represent two distinct approaches to social inquiry. Quantitative research deals with numerical data and statistical analysis, aiming to test hypotheses and establish generalizable patterns[1]. It employs methods such as surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis of existing data[3]. Qualitative research, on the other hand, focuses on non-numerical data like words, images, and sounds to explore subjective experiences and attitudes[3]. It utilizes techniques such as interviews, focus groups, and observations to gain in-depth insights into social phenomena[1].

The debate between quantitative and qualitative approaches has evolved into a recognition of their complementary nature. Mixed methods research, which combines both approaches, has gained prominence in social sciences. This approach allows researchers to leverage the strengths of both methodologies, providing a more comprehensive understanding of complex social issues[4]. For instance, a study might use surveys to gather quantitative data on trends, followed by in-depth interviews to explore the underlying reasons for these trends.

When choosing research methods, several practical considerations come into play. Researchers must consider the type of data required, their skills and resources, and the specific research context[4]. The nature of the research question often guides the choice of method. For example, if the goal is to test a hypothesis or measure the prevalence of a phenomenon, quantitative methods may be more appropriate. Conversely, if the aim is to explore complex social processes or understand individual experiences, qualitative methods might be more suitable[2].

It’s important to note that the choice of research method is not merely a technical decision but also reflects epistemological and ontological assumptions about the nature of social reality and how it can be studied[1]. Researchers should be aware of these philosophical underpinnings when selecting their methods.

In conclusion, the choice of research method in social research is a crucial decision that requires careful consideration of research objectives, practical constraints, and philosophical assumptions. By thoughtfully selecting appropriate methods, researchers can ensure that their studies contribute meaningful insights to the field of social sciences.

References:

Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2010). Research methods: A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson Education.

Scribbr. (n.d.). Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods.

Simply Psychology. (2023). Qualitative vs Quantitative Research: What’s the Difference?

National University. (2024). What Is Qualitative vs. Quantitative Study?

Citations:

[1] https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-quantitative-research/

[2] https://researcher.life/blog/article/qualitative-vs-quantitative-research/

[3] https://www.simplypsychology.org/qualitative-quantitative.html

[4] https://www.nu.edu/blog/qualitative-vs-quantitative-study/

[5] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3327344/

[6] https://www.thesoundhq.com/qualitative-vs-quantitative-research-better-together/

[7] https://www.fullstory.com/blog/qualitative-vs-quantitative-data/

[8] https://accelerate.uofuhealth.utah.edu/improvement/understanding-qualitative-and-quantitative-approac -

Guide SPSS How to: Correlation

Calculating Correlation in SPSS

Step 1: Prepare Your Data

- Enter your data into SPSS, with each variable in a separate column.

- Ensure your variables are measured on an interval or ratio scale for Pearson’s r, or ordinal scale for Spearman’s rho

Step 2: Access the Correlation Analysis Tool

- Click on “Analyze” in the top menu.

- Select “Correlate” from the dropdown menu.

- Choose “Bivariate” from the submenu

Step 3: Select Variables

- In the new window, move your variables of interest into the “Variables” box.

- You can select multiple variables to create a correlation matrix

Step 4: Choose Correlation Coefficient

- For Pearson’s r: Ensure “Pearson” is checked (it’s usually the default).

- For Spearman’s rho: Check the “Spearman” box

Step 5: Additional Options

- Under “Test of Significance,” select “Two-tailed” unless you have a specific directional hypothesis.

- Check “Flag significant correlations” to highlight significant results

Step 6: Run the Analysis

- Click “OK” to generate the correlation output

Interpreting the Results

Correlation Coefficient

- The value ranges from -1 to +1.

- Positive values indicate a positive relationship, negative values indicate an inverse relationship[1].

- Strength of correlation:

- 0.00 to 0.29: Weak

- 0.30 to 0.49: Moderate

- 0.50 to 1.00: Strong

Statistical Significance

- Look for p-values less than 0.05 (or your chosen significance level) to determine if the correlation is statistically significant.

Sample Size

- The output will also show the sample size (n) for each correlation.

Remember, correlation does not imply causation. Always interpret your results in the context of your research question and theoretical framework.

To interpret the results of a Pearson correlation in SPSS, focus on these key elements:

- Correlation Coefficient (r): This value ranges from -1 to +1 and indicates the strength and direction of the relationship between variables

- Positive values indicate a positive relationship, negative values indicate an inverse relationship.

- Strength interpretation:

- 0.00 to 0.29: Weak correlation

- 0.30 to 0.49: Moderate correlation

- 0.50 to 1.00: Strong correlation

- Statistical Significance: Look at the “Sig. (2-tailed)” value

- If this value is less than your chosen significance level (typically 0.05), the correlation is statistically significant.

- Significant correlations are often flagged with asterisks in the output.

- Sample Size (n): This indicates the number of cases used in the analysis

Example Interpretation

Let’s say you have a correlation coefficient of 0.228 with a significance value of 0.060:

- The correlation coefficient (0.228) indicates a weak positive relationship between the variables.

- The significance value (0.060) is greater than 0.05, meaning the correlation is not statistically significant

- This suggests that while a small positive correlation was observed in the sample, there’s not enough evidence to conclude that this relationship exists in the population

- Remember, correlation does not imply causation. Always interpret results in the context of your research question and theoretical framework.

-

Concepts and Variables

Concepts and variables are important components of scientific research (Trochim, 2006). Concepts refer to abstract or general ideas that describe or explain phenomena, while variables are measurable attributes or characteristics that can vary across individuals, groups, or situations. Concepts and variables are used to develop research questions, hypotheses, and operational definitions, and to design and analyze research studies. In this essay, I will discuss the concepts and variables that are commonly used in scientific research, with reference to relevant literature.

One important concept in scientific research is validity, which refers to the extent to which a measure or test accurately reflects the concept or construct it is intended to measure (Carmines & Zeller, 1979). Validity can be assessed in different ways, including face validity, content validity, criterion-related validity, and construct validity. Face validity refers to the extent to which a measure appears to assess the concept it is intended to measure, while content validity refers to the degree to which a measure covers all the important dimensions of the concept. Criterion-related validity involves comparing a measure to an established standard or criterion, while construct validity involves testing the relationship between a measure and other related constructs.

Another important concept in scientific research is reliability, which refers to the consistency and stability of a measure over time and across different contexts (Trochim, 2006). Reliability can be assessed in different ways, including test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and internal consistency. Test-retest reliability involves measuring the same individuals on the same measure at different times and examining the degree of consistency between the scores. Inter-rater reliability involves comparing the scores of different raters who are measuring the same variable. Internal consistency involves examining the extent to which different items on a measure are consistent with each other.

Variables are another important component of scientific research (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Variables are classified into independent variables, dependent variables, and confounding variables. Independent variables are variables that are manipulated by the researcher in order to test their effects on the dependent variable. Dependent variables are variables that are measured by the researcher in order to assess the effects of the independent variable. Confounding variables are variables that may affect the relationship between the independent and dependent variables and need to be controlled for in order to ensure accurate results.

In summary, concepts and variables are important components of scientific research, providing a framework for developing research questions, hypotheses, and operational definitions, and designing and analyzing research studies. Validity and reliability are important concepts that help to ensure the accuracy and consistency of research measures, while independent, dependent, and confounding variables are important variables that help to assess the effects of different factors on outcomes. Understanding these concepts and variables is essential for conducting rigorous and effective scientific research.

-

Immersiveness Measuring with Scales

Immersiveness is a key aspect of film that refers to the degree to which viewers feel engaged and absorbed in the cinematic experience (Tamborini, Bowman, Eden, & Grizzard, 2010). Measuring immersiveness in film can be challenging, as it is a subjective experience that can vary across individuals and films (Calleja, 2014). In this discussion, I will explore some of the methods that have been used to measure immersiveness in film, with reference to relevant literature.

One way to measure immersiveness in film is through the use of self-report measures, which ask viewers to rate their subjective experience of immersion. For example, Tamborini et al. (2010) developed a multidimensional scale of perceived immersive experience in film, which includes items related to spatial presence (e.g., “I felt like I was in the same physical space as the characters”), narrative transportation (e.g., “I was completely absorbed in the story”), and emotional involvement (e.g., “I felt emotionally connected to the characters”). Participants rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater levels of immersiveness. Other self-report measures of immersiveness include the Immersive Experience Questionnaire (Chen, Huang, & Huang, 2020) and the Immersion Questionnaire (Jennett et al., 2008).

Another way to measure immersiveness in film is through the use of physiological measures, which assess changes in bodily responses associated with immersion. For example, Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) is a measure of the electrical conductance of the skin that can indicate arousal and emotional responses (Kreibig, 2010). Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is another measure that can be used to assess physiological changes associated with immersion, as it reflects the variability in time between successive heartbeats, and is influenced by both parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system activity (Laborde, Mosley, & Thayer, 2017).

In addition to self-report and physiological measures, behavioral measures can also be used to assess immersiveness in film. For example, eye-tracking can be used to measure the extent to which viewers focus their attention on different elements of the film, such as the characters or the environment (Bulling et al., 2016). Eye-tracking data can also be used to infer cognitive processes associated with immersion, such as mental workload and engagement (Munoz-Montoya, Bohil, Di Stasi, & Gugerty, 2014).

Overall, measuring immersiveness in film is a complex and multifaceted process that involves subjective, physiological, and behavioral components. Self-report measures are commonly used to assess viewers’ subjective experience of immersion, while physiological measures can provide objective indicators of bodily responses associated with immersion. Behavioral measures, such as eye-tracking, can provide insights into cognitive processes associated with immersion. Combining these different methods can help to provide a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of immersiveness in film.

References

Bulling, A., Mansfield, A., & Elsden, C. (2016). Eye tracking and the moving image. Springer.

Calleja, G. (2014). In-game: From immersion to incorporation. MIT Press.

Chen, Y.-W., Huang, Y.-J., & Huang, C.-H. (2020). The Immersive Experience Questionnaire: Scale development and validation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(1), 49-61.

Jennett, C., Cox, A. L., Cairns, P., Dhoparee, S., Epps, A., Tijs, T., & Walton, A. (2008). Measuring and defining the experience of immersion in games. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 66(9), 641-661.

Kreibig, S. D. (2010). Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 394-421.

Laborde, S., Mosley, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2017). Heart rate variability and cardiac vagal tone in psychophysiological research–recommendations for experiment planning, data analysis, and data reporting. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 213.

Munoz-Montoya, F., Bohil, C. J., Di Stasi, L. L., & Gugerty, L. (2014). Using eye tracking to evaluate the cognitive workload of image processing in a simulated tactical environment. Displays, 35(3), 167-174.

Tamborini, R., Bowman, N. D., Eden, A., & Grizzard, M. (2010). Organizing the perception of narrative events: Psychological need satisfaction and narrative immersion. In P. Vorderer, D. Friedrichsen, & J. Bryant (Eds.), Playing video games: Motives, responses, and consequences (pp. 165-184). Routledge.

-

Cultivation Theory

Cultivation theory is a theoretical framework in the field of media studies that explains how long-term exposure to media can shape people’s perceptions of reality. According to this theory, the more an individual is exposed to media content, the more their perceptions of reality become shaped by the media, resulting in the cultivation of shared beliefs and attitudes among heavy media users.

The theory has been widely studied and applied in the field of media studies. For example, a study by Gross and colleagues (2004) investigated the impact of television on people’s perceptions of crime. The study found that heavy viewers of crime dramas were more likely to overestimate the prevalence of crime in society and to have a more negative view of the police than light viewers. The study provided evidence for the impact of media exposure on people’s perceptions of reality, as predicted by cultivation theory.

Another study that has applied cultivation theory to the analysis of media effects on young people is the study by Lee and colleagues (2014). The study investigated the impact of media exposure on young people’s attitudes towards appearance and body image. The results of the study showed that heavy users of social media and television were more likely to have negative attitudes towards their own bodies and to compare themselves unfavorably to others. The study supported the idea that media exposure can shape attitudes and beliefs over time, as predicted by cultivation theory.

Critics of cultivation theory have argued that the theory may overestimate the impact of media on individuals and underestimate the role of other factors, such as socialization and personal experiences. Furthermore, some critics contend that cultivation theory tends to focus on the effects of media on particular groups of people, such as heavy viewers of violent content, rather than on the wider population.

Despite these criticisms, cultivation theory remains a useful framework for analyzing media effects on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. One way that cultivation theory has been refined is through the concept of “cultural indicators”, which refers to the recurring themes and messages in media content that can shape people’s perceptions of reality (Gerbner, 1969).

In conclusion, cultivation theory is a valuable theoretical framework that has been used to explain the impact of media on people’s perceptions of reality over time. While the theory has been criticized for its focus on particular groups and its potential to overestimate the impact of media, it remains a useful tool for analyzing media effects on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

Reference

Gerbner, G. (1969). Toward “cultural indicators”: The analysis of mass mediated public message systems. AV Communication Review, 17(2), 137-148.

Gross, K., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (2004). “You’re it”: Reality TV, cruelty, and privacy. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48(3), 387-402.

Lee, M., Lee, H., & Moon, S. I. (2014). Social media, body image, and self-esteem: A study of predictors and moderators among young women. Journal of Health Communication, 19(10), 1138-1153.

Morgan, M., & Shanahan, J. (2010). The state of cultivation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 54(2), 337-355.

Shrum, L. J. (2012). The psychology of entertainment media: Blurring the lines between entertainment and persuasion. Routledge.

Signorielli, N. (2014). Cultivation theory. The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies, 1-12.

Tukachinsky, R., Slater, M. D., & Choi, Y. H. (2016). The role of media exposure in agenda setting: A longitudinal study. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(1), 39-60.

-

Indepth Interview

Qualitative research interviews are a method used to gather information about people’s experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions. There are several different types of qualitative research interviews that you can use, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Here’s an overview of the most common methods:

- Structured Interviews: Structured interviews are highly standardized and follow a pre-determined set of questions. This type of interview is often used in surveys, and is best for gathering quantitative data.